“Charting innovative scenarios for the future of knowledge creation and dissemination in the arts and humanities” –metaLAB

Last Thursday I visited openLAB, a showcase / open house for metaLAB at Harvard. They’re working on some fascinating ideas, projects that will have bearing on learning, inquiry, curation, and inter-disciplinary collaboration.

Some of the projects

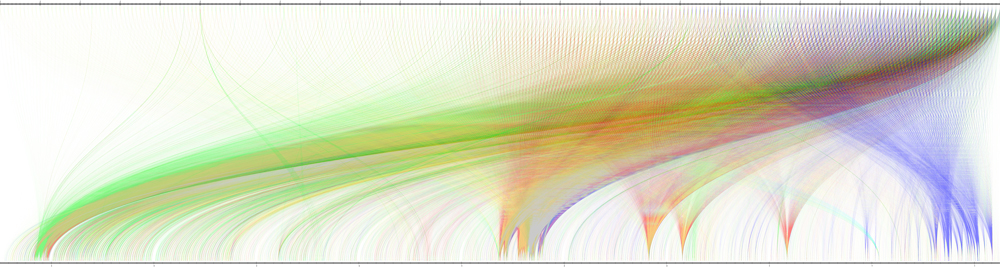

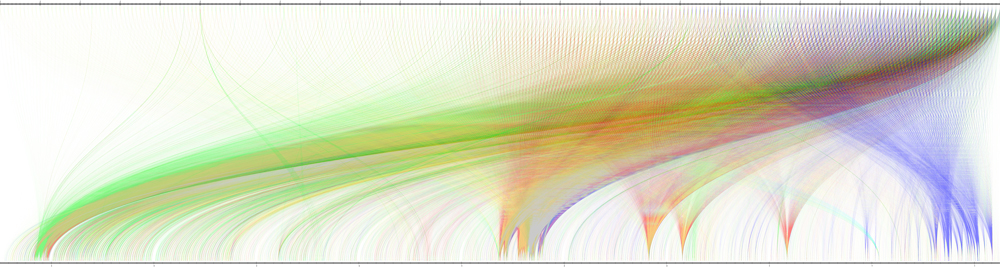

Library Observatory: Harvard Accessions: using Digital Public Library of America (DPLA) API, this project tracks acquisition and accession of non-English items at the Harvard Library, rendering a curious and beautiful graphic representation across time, language, and events. Another piece juxtaposes accession with publication date, a swirling chronological visual narrative.

Zeega: Zeega.org is focused on inventing new forms of interactive storytelling and documentaries, a creation tool and platform combining editorial and design tools using HTML5, with JS libraries such as Backbone and Popcorn. (See http://mozillapopcorn.org/ for Mozilla’s work in this area.). You can click and drag content, collaborate with and through massive collections such as vimeo and Flickr, among others, and in general, start to make video work like the web (Mozilla). I am eager to try this with students.

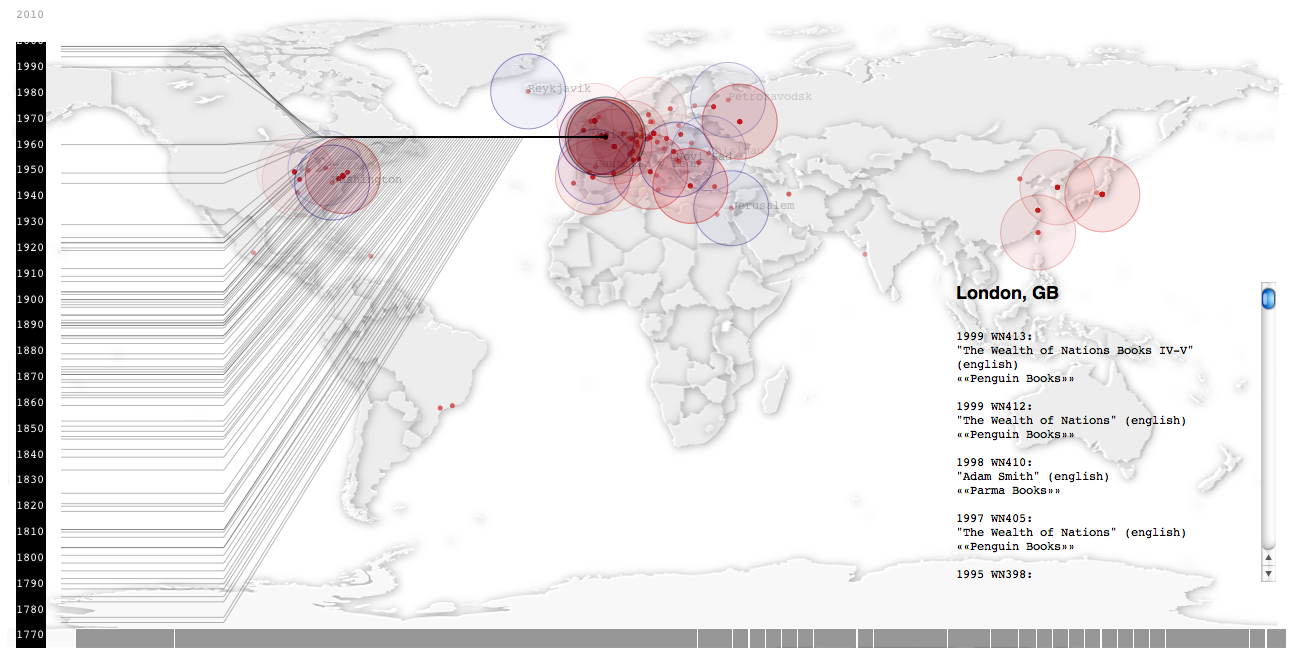

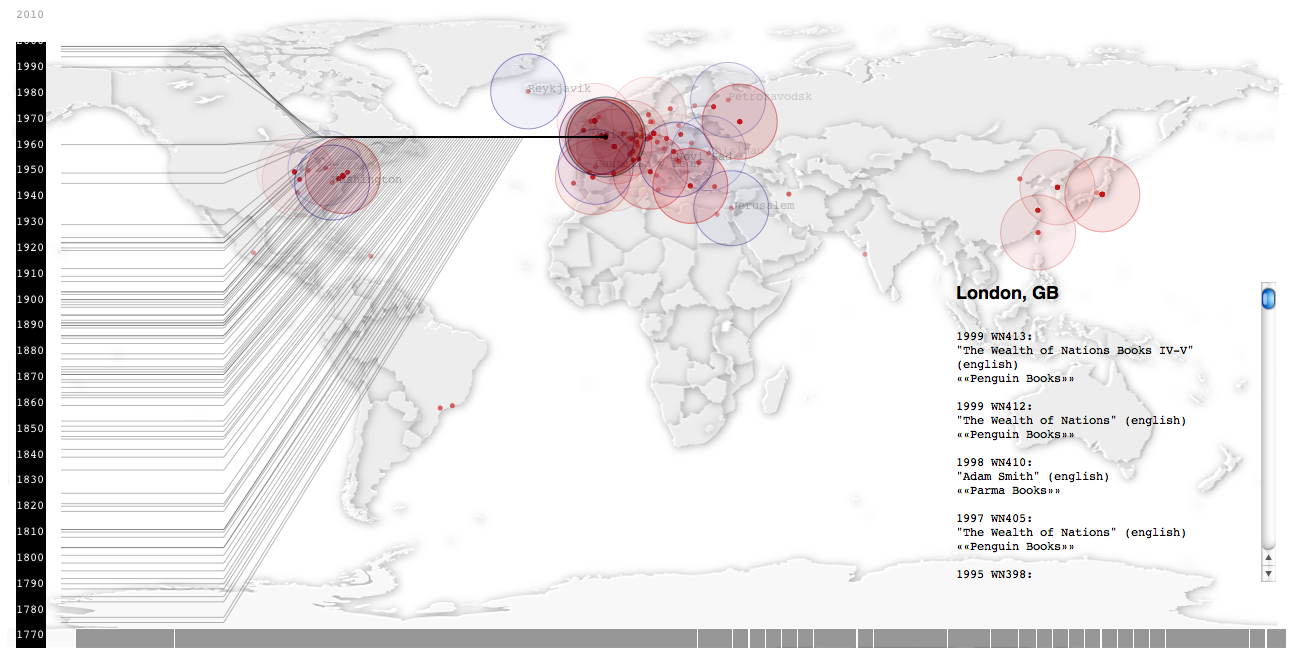

A Wealth of Nations: The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith’s book mapped to create a global geo-spatial representation of publication since 1776.

Digital Ecologies at Arnold Arboretum: Although just emerging in form, this initiative sounds especially promising for its embrace of a multidisciplinary approach that combines sciences, design, curation, and digital media. Project leader Kyle Parry writes, “We are asking what visitor experiences become possible when we integrate information and media ecologies into a living landscape teeming with natural and human histories.” This project, he notes, is “Conceptually situated at the intersection of nature and networks, landscape and media design, and science and aesthetics…”.

_____ _____

Throughout the evening, I participated in some great conversations, moving around the rooms, stumbling upon informal clusters of people gathered around visualizations, making observations, listening to presenters, and asking questions. Lots of good activity. One attendee seemed dismayed, though, that there weren’t enough Answers. And in truth, perhaps there were a few others who also longed for firmer conclusions, for tenable defenses. My sense is that answering questions was not the evening’s purpose, however.

Many of the openLAB projects looked at data artifacts or larger data patterns afforded by access to Library Cloud or DPLA. These works ask us to step back from the trees to see the forest. And as a result of this perspectival shift, viewers were curious. What is that contour and then sudden swirl in the Early Modern Collections visualization, and what does it say about the collecting (and funding) preferences of the institution? What is this anomaly is here, this lone instance of The Wealth of Nations in Argentina in the early 1800s? Why is it there?

These are “traces,” suggested metaLAB’s Mathew Battles. They are “bread crumbs” and paths we can follow, curate and, I would add, cultivate.

I like this language and imagery. It serves metaLAB projects well. In these works we start to see the nuances of data, contours and overlaps and intersections that we never would have seen. The odd thing is that these are patterns that have always been there, in front of us, but not visible. And strangely, we sometimes need to see a big picture in order to discover a small detail. We encounter traces, residues, anomalies and patterns, and these moments of observation and inquiry become starting points for participation and collaboration, and for more questions. Resisting the Answer, then, becomes a beginning at metaLAB, not an end.

Library Observatory and A Wealth of Nations images from metaLAB.

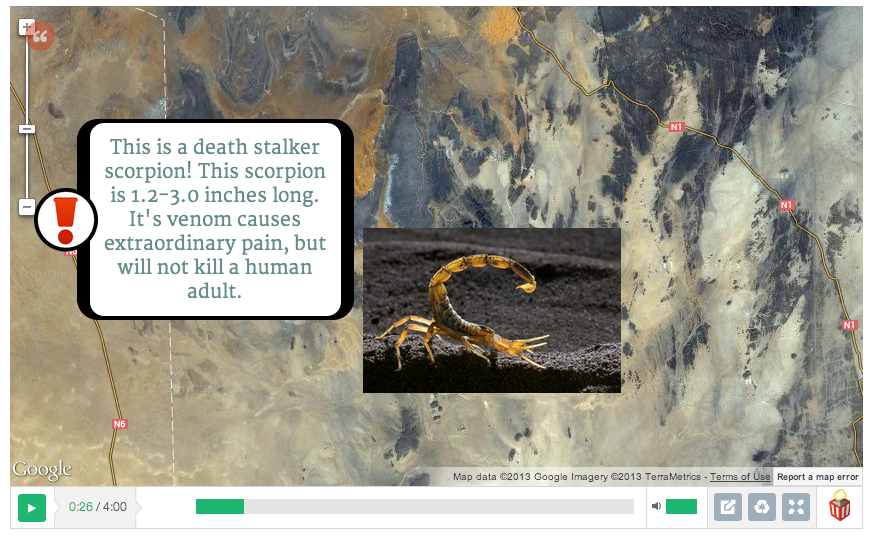

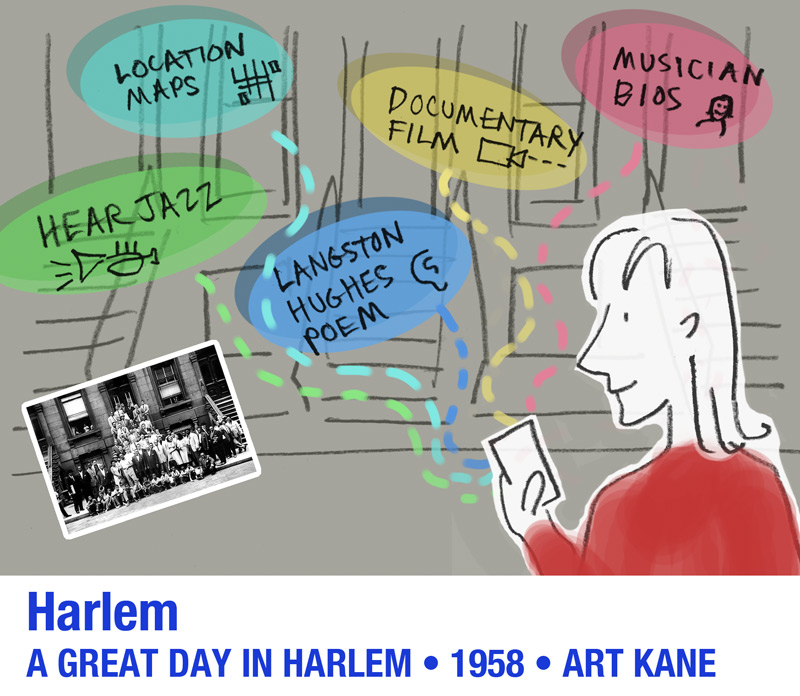

We wanted to see what students would do if they were given the chance to curate a local museum and share their experiences with peers back at school. Karin Stack, local charter school art and digital teacher at Berkshire Arts and Technology School (BART), agreed to bring several teams of middle school students to the Berkshire Museum in Pittsfield, MA.

We wanted to see what students would do if they were given the chance to curate a local museum and share their experiences with peers back at school. Karin Stack, local charter school art and digital teacher at Berkshire Arts and Technology School (BART), agreed to bring several teams of middle school students to the Berkshire Museum in Pittsfield, MA. We’ll have more extensive data and feedback to report in the near future!

We’ll have more extensive data and feedback to report in the near future!